Science and scholarship before and during the war – race research and ideological subservience

The search for the “race gene”: The German Research Foundation provided a variety of support to research projects by doctors, biologists and anthropologists that were intended to scientifically justify the racial policies of the NS regime, and financed inhuman research on prisoners of war and camp prisoners.

- Emphasis on NS ideolog(externer Link)

- “Blood samples of over 200 persons of extremely varied racial types” – funding of heredity researc(externer Link)

- “Race research” in the 1920s and under National Socialis(externer Link)

- “Good fortune for research” – how science and scholars used the NS doctrin(externer Link)

- “The sword must be well sharpened” – Courting international recognitio(externer Link)

Emphasis on NS ideology

Research projects in medicine and anthropology in particular, together with their funding, show the close and lethal interconnection between the state and science. The German Research Foundation and the Reichsforschungsrat provided both financial support and encouragement to researchers in order to legitimise state racial policies with the help of scientific expertise. The researchers and their research, which included human experimentation in concentration camps and institutions, were not simply “victims” of the National Socialist regime in this process, who were “forced” to perform inhuman research. On the contrary, many doctors, biologists and anthropologists willingly gave themselves in service to the eugenics, race and population policies of National Socialism.

The National Socialist distinction between “inferior” and “superior” races had its roots in the Weimar Republic. In Germany as in many other countries, “racial hygiene” and “human heredity” were considered legitimate fields of research. The Notgemeinschaft, reflecting the spirit of the age, set up the “Community Project for Race Research” in 1928.

The humanities, on the other hand, underwent a loss of status in the National Socialist era. While the humanities and social sciences still received a 30 percent share of the Notgemeinschaft budget at the end of the 1920s, this fell to 22 percent under National Socialism. In the Third Reich, from 1933 on funding priorities also shifted in the humanities in favour of new, ideology-related areas. The intention was to underpin German aspirations to dominance in Europe with historical, linguistic, ethnological and cultural studies. Funding priorities were now placed on pre- and early history or historical and political research into “Grenz- und Auslandsdeutschtum” (“Germanness” on the borders and in countries with high numbers of German immigrants). In the area of linguistic sciences, the Notgemeinschaft concentrated on funding major projects such as the “Meister Eckhart” edition and the “Sprachatlas” (language atlas), which tied up Germanistic and literary studies resources for many years and left little financial scope for individual research.

The funding of the “General Plan East” by the Reichsforschungsrat is a further example of the humanities providing a rationale for ideological actions. The General Plan provided a rationale for the ethnic homogenisation of large areas of Eastern Europe by means of the resettlement of the local population and settlement of Germans. The DFG has dedicated an exhibition to the critical reappraisal of the “General Plan East,” which was created as part of a research project on the history of the DFG, and has been on display as a travelling exhibition since 2006.

“Blood samples of over 200 persons of extremely varied racial types” – funding of heredity research

Second report of Verschuer to the Notgemeinschaft, March 1944

© Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde: R 73/15342, Blatt 64, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

The German Research Foundation also funded research by the geneticist Otmar von Verschuer under National Socialism. His interim reports to the Notgemeinschaft from the years 1943 and 1944, which relate to the project with the title “Specific Proteins,” leave no doubt that Otmar von Verschuer received blood samples from prisoners in the Auschwitz Concentration Camp from concentration camp doctor Josef Mengele.

The funding of such projects by the German Research Foundation was not an isolated incident. It and/or the Reichsforschungsrat funded a large number of projects that included human experimentation in concentration camps or institutions. In 2006, as a reminder of the participation and involvement of the predecessor organisation to the DFG in crimes under National Socialism, the DFG erected a memorial in front of its main entrance. It consists of two stelae. The first stele reproduces the Second Interim Report from Otmar von Verschuer’s “Spezifische Eiweißkörper” project. On the second, US historian Fritz Stern makes a plea for German science to be given “a second chance in a new Europe” despite the atrocities under National Socialism.

Third report of Verschuer to the Notgemeinschaft, October 1944

© Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde: R 73/15342, Blatt 47, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Otmar von Verschuer was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics from 1942. There were two research projects under his oversight in which he made use of his former Frankfurt assistant, Dr. Josef Mengele, who had been a camp doctor in Auschwitz since 1943: the “Proteins” project and investigations by his colleague (and former Notgemeinschaft fellow) Karin Magnussen on the genetics of eye pigmentation, entitled “Eye Colour”. The funding proposals were approved in August and September 1943 respectively by the head of the expert division of the Reichsforschungsrat, Ferdinand Sauerbruch.

The goal of von Verschuer’s project “Specific Proteins” was a new serological diagnosis of race in order to supplement or replace the more elaborate diagnostic methods previously used for paternity or race reviews. The definition of “race” was a key question in National Socialist policy, the answer to which was still open even in 1944. The blood samples were from concentration camp prisoners in Auschwitz and were sent to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute headed by Otmar von Verschuer for analysis. It its not possible to determine with certainty whether Otmar von Verschuer knew the origin of the specimens or the conditions under which they were acquired. However, the evidence that he must have known is overwhelming.

The intention behind Magnussen's investigations was to apply the knowledge acquired about the genetics of eye pigmentation and iris structure to race diagnosis and replace outdated eye-colour tables. Mengele sent at least 14 heterochromous (differently coloured) pairs of eyes which he had removed from members of Sinti families in Auschwitz to Otmar von Verschuer. Whether Josef Mengele had previously killed the pairs of twins in order to be able to make their eyes available to his colleague Magnussen is not proven.

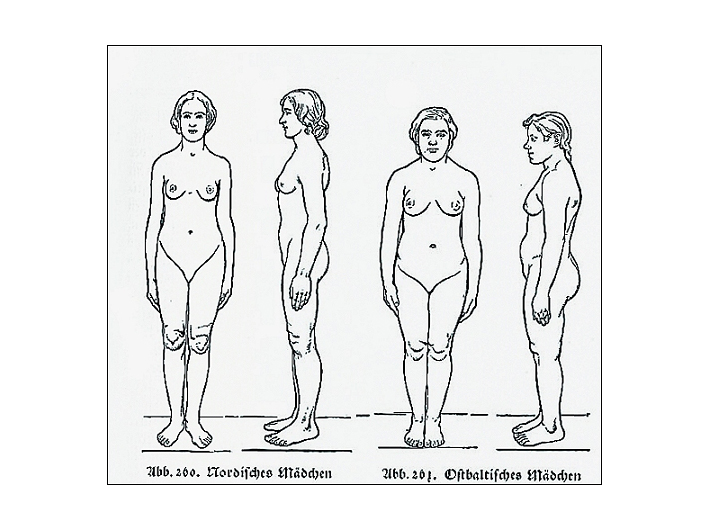

Otmar von Verschuer and Karin Magnussen were two of a number of researchers who had made it their goal to determine “racial types” based on – supposedly – scientific characteristics. The categorisation of people into “Aryan” and “non-Aryan” races was a part of the National Socialist value system, and human heredity, eugenics and race research therefore numbered among the disciplines that had been favoured by National Socialist science policy since 1933. These fields, in particular, clearly show how government instrumentalised science, and how science willingly implemented ideologically driven aspirations.

“Race research” in the 1920s and under National Socialism

Picture from Hans F.K. Günthers "Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes", 1930

However, race research under National Socialism did not simply appear unexpectedly. In the 1920s, after the experiences of the First World War and in view of economic and also social problems, a fear developed in many countries about the decline of their own culture and of biological degeneration. The result of this fear was deliberations on how healthy hereditary material could be boosted for the genetic improvement of one’s “own race”. Firstly through so-called “positive” eugenics, i.e., an increase in the birthrate of “Erbgesunde” (those of “healthy heredity”) and “Tüchtige” (capable and hard-working), and secondly through “negative eugenics”, birth control in “Erbkranke” (hereditary defectives). In view of such discussions in society and science, in Germany as in many other countries “racial hygiene” and “human heredity” were perceived as a legitimate field of research. Science and research pursued, for example, the questions of the extent to which criminality, alcoholism or intellectual and physical disabilities were genetically determined and heritable.

Many nations recorded the composition of their native population to take stock of the state of health of their own populations. The Notgemeinschaft also followed this fatal trend in 1928 when it called the “Community Projects for Race Research” into being. They initially concentrated on a racial inventory of the German population with the help of anthropological investigations of physical characteristics. The work was overseen by internationally renowned anthropologist and Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology Eugen Fischer. However, this method was soon in scientific decline and in 1930 the Notgemeinschaft therefore expanded its work – with funding sources including the US Rockefeller Foundation – to include hereditary pathological investigations.

The criminal-biology-based twin research by the head of the German Research Institute for Psychiatry, Ernst Rüdin, was included in the Community Projects in 1930. The intention was to prove a hereditary factor in criminal behaviour. The attempt that lay behind these research projects – to find a connection between criminal dispositions and hereditary defects – increasingly became the focus of attention, because scientific inquiry and political interests overlapped here at a highly controversial point.

According to National Socialist race ideology, there should no longer be a place for “Gemeinschaftsfremde” (people alien to the community) in the “Volksgemeinschaft” (community of the Volk). What was meant by this was Jews – regarded as a “race” and not as a religious community – who were allegedly trying to destroy the German “master race”, together with “gypsies” and other “inferior groups”. Offspring who were of “healthy heredity” and “Aryan” should be encouraged, and people defined as hereditary defectives and non-Aryan should be decreased by “extermination”. The implementation of these postulates was a central component of the NS injustice system. The main difference compared with all other countries was the extremely rapid, thorough implementation of the race-hygiene utopia – on an unfathomable scale.

Several laws supported the implementation of the National Socialist race ideology. On 1 January 1934 the “Law for the contraception of progeny with hereditary defects” which had been passed in July 1933 entered into force. It provided for the forced sterilisation of persons with “congenital idiocy, schizophrenia, (...) insanity, hereditary epilepsy, blindness or deafness, hereditary St Vitus' Dance, severe physical deformity and severe alcoholism”. The Nuremberg Laws passed in 1935 comprised the law “zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre” (for the protection of German blood and honour), which prohibited marriage and extra-marital sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews, and the Reichsbürgergesetz (Reich Citizenship Law), in which it was specified that only “citizens of German or related blood” could be Reich citizens.

Science and scholarship – including the German Research Foundation – contributed in various ways to the implementation of these laws. Only a few months after the commencement of the “Law for the contraception of progeny with hereditary defects”, the Reich Ministry of the Interior enforced the rule at the Notgemeinschaft that the Director of the Health Department, Arthur Gütt, should be consulted in the allocation of resources in order to ensure that “racial hygiene and population policy issues are dealt with everywhere in accordance with uniform points of view”. In June 1934, the German Research Foundation complied with Gütt's request to assess files and reports of the Erbgesundheitsgerichte (Hereditary Health Courts), which decided on compulsory sterilisation, using research projects which the Foundation funded. At the start of 1936, Arthur Gütt was appointed chair of the Expert Committee for Human Genetics. The proposals were forwarded to him and processed by his colleague, the sterilisation activist and later co-organiser of the euthanasia operation “Action T4”, Herbert Linden.

The Memorial and Information Centre for the victims of the National Socialist “euthanasia” murders was opened in September 2014. The DFG knowledge transfer project “To remember means to commemorate and inform” developed the materials for the interactive exhibition.

Research projects aimed at developing guidelines for differentiating hereditary and non-hereditary deformities received funding so that the sterilisation law could be implemented more easily. For example, the German Research Foundation endorsed a funding proposal on “systematic family investigations of nervous diseases”, which in the opinion of the applicant were not yet adequately researched. Researchers thereby took a key role in the recording and segregation of Jews, Sinti and Roma, “Rhineland bastards”, “hereditary defectives”, “anti-socials” and homosexuals, and the Notgemeinschaft financed the associated projects.

One example is the work of the Rassenhygienische Forschungsstelle (Racial Hygiene Research Unit) under Robert Ritter, who was involved in the documentation of the “gypsies” to be deported during the war – work which was funded by the German Research Foundation and the Reichsforschungsrat (RFR), Expert Division on Population Policy. The RFR supported projects that dealt with questions of the heritability of “anti-social” behaviour, “psychopathy” and lineage analysis and supposedly inherited characteristics in Sinti and Roma.

The German Research Foundation also funded salaries for research employees of the newly established Poliklinik für Erb- und Rassenpflege (Polyclinic for Hereditary and Racial Hygiene), the tasks of which including preparing hereditary biology-based reviews for various Hereditary Health Courts, the purpose of which was to legitimise compulsory sterilisation.

Since the research field of heredity and race research was only occupied by a few people, there was close contact between the applicants and reviewers. The researchers Eugen Fischer and Ernst Rüdin were consulted most frequently in the area of heredity and race research for the review of proposals, and therefore had a long-term influence on the funding of heredity research. In line with the proposals selected, the German Research Foundation gave increasing support to research projects that investigated the role of heredity in deformities.

It was Ernst Rüdin, co-drafter of the “Law for the contraception of progeny with hereditary defects”, more than anyone, who used his own research programme as a yardstick for the evaluation of research proposals in the field of heredity and race research. Eugen Fischer, Ernst Rüdin and Otmar von Verschuer ensured that it was primarily junior staff known to them who received funding. The principle of the internal recruitment of junior researchers created homogeneity in the group of fellowship recipients.

“Good fortune for research” – how science and scholars used the NS doctrine

Funding grant by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for the project

© Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde: R 73 / 12517, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

By 1933 at the latest, a majority of German society approved the idea that there were “inferior” human lives which needed to be “extinguished”. This ideology in the spirit of the “Volksgemeinschaft” (community of the Volk) increased many researchers’ willingness to breach what were in fact universal ethical rules that had previously applied. Scientific motivations also played a role. Human experimentation seemed to be the simplest and most precise way to solve particular research questions – say, about the efficacy of certain medicines. In the eyes of many researchers, certain detainees or patients were no longer human beings, but “experimental material” that was now more readily available.

The Reichsforschungsrat supported a series of projects “critical to the war” on “ancestral heredity” such as “cold experiments” on prisoners in the Dachau concentration camp and trials of the chemical weapon mustard gas on prisoners in the Natzweiler concentration camp.

The funding of a project carried out by Hans Kummerlöwe was also a part of this picture. The project was funded by the German Research Foundation with a research grant for “anthropological surveys on Polish prisoners of war”. In a latter dated 25 June 1940, the applicant described the importance of his research project. He said that the Anthropological Museum of the Wissenschaftliche Staatsmuseum in Vienna was planning

“comprehensive anthropological surveys on prisoners of war further to its previous investigations on Polish people, since around 30,000 prisoners of war from a great variety of peoples, races and colours have arrived in the Kaisersteinbruch camp. (...) I ask that it be noted that what is involved is not a normal project, but a uniquely favourable opportunity for the anthropologists here, and for German science as a whole.”

Such a “unique opportunity”, together with other factors, resulted in eugenicists, geneticists, doctors, brain researchers, psychiatrists, psychologists, criminal biologists and anthropologists willingly dedicating their expert knowledge in the service of the new regime. In line with their own personal conviction, many believed that their purpose lay in working on precisely those scientific topics that could best contribute to the success of the goals of National Socialism – domination in Europe and a “pure-bred” master race. They placed their projects in a socio-political context and wanted to induce the state to implement population policies guided by what they viewed as science.

Science and scholarship were expected to legitimate NS policies – as Otmar von Verschuer wrote in 1937.

“However, it is important that our race policies – including the Jewish issue – should be given an objective scientific background, that is also recognised in broader circles.”

Many researchers saw National Socialism as the opportunity to put into practice, through their own scientific work, the racist and anti-Semitic convictions they had developed even prior to 1933, in actual population policy measures. In a speech in praise of National Socialism in 1934, Ernst Rüdin wrote:

“It is only thanks to the political works of Adolf Hitler that the significance of racial hygiene has been revealed to all alert Germans, and it was only through him that our dream of over thirty years became reality: to be able to put racial hygiene into practice.”

Eugen Fischer similarly lauded National Socialist racial policies in 1943:

“It is a special and rare good fortune for a piece of research which is, per se, theoretical, if it coincides with an era when the general Weltanschauung greets it with approval, and indeed where its practical results are immediately welcome as the foundation of state measures.”

The German Research Foundation – already committed to NS race ideology through the introduction of the “Community Projects on Race Research” – very explicitly supported the NS regime through an academic “Kundgebung”, a rally in Königsberg in May 1933, at which Eugen Fischer was the main speaker. Fischer stressed the close relationship between scientific heredity research and the baselines of the National Socialist postulates on racial hygiene. He overestimated his scientific achievements enormously in anticipation of the opportunities that would be on offer in the new NS state. He postulated that researchers in twin research

“have incontrovertibly determined the heritability of almost all hereditary diseases. The progress of the last 10 years is so great in this area that I would like to say, taking complete responsibility, that we have a completely secure foundation for all potential population policy measures.”

In the course of the presentation, he gave examples from “Bevölkerungslehre” (population theory) that pointed to “a decline of our Volk”. His conclusion was that

“We must attempt to exterminate the diseased lines and to prevent their reproduction.”

“The sword must be well sharpened” – Courting international recognition

Many German researchers were internationally renowned before the National Socialists took power. Otmar von Verschuer, and Ernst Rüdin and his Research Institute for Psychiatry, for example, were considered to be excellent researchers. Their work on the inheritance of racial characteristics and Verschuer's twin research were in keeping with the international trend. Discoveries in human genetics made it increasingly evident, however, that the inheritance of genetically (co-)determined diseases and disabilities was not as simple as had still been assumed when the Erbschutzgesetze (laws for the protection of heredity) were drafted.

Until the 1930s, German blood group research had been very significant in international science. From the mid-1930s, Germany became more and more isolated with its racial theories compared with international research on heredity. In the “Edinburgh Charter” of 1939, the International Congress of Geneticists protested against the “unscientific doctrine that good and bad genes [were] the monopoly of certain peoples and persons”.

Many researchers in the life sciences were aware that in supporting mandatory eugenics measures they found themselves on shaky ground scientifically, and might also encounter resistance in the international arena. In his article “Racial Hygiene as a Science and Responsibility of the State”, Otmar von Verschuer expressed his fears:

“There are many efforts under way to attack hereditary and racial hygiene in National Socialist German via science – the sword of our science must therefore be well sharpened and wielded well!”

Further information

“GEPRIS Historisc(externer Link)” (in German only) is the comprehensive information portal provided by the DFG that makes the history of the DFG and of research between 1920 and 1945 publicly accessible.

Information on literatur(Download) used and sources.