The origins of the Notgemeinschaft

- “In order to avert a complete collapse of German science and scholarship(externer Link)

- The situation of science and scholarship in Germany after the First World Wa(externer Link)

- The foundation of the “Stifterverband” (Donors’ Association), December 192(externer Link)

“In order to avert a complete collapse of German science and scholarship”

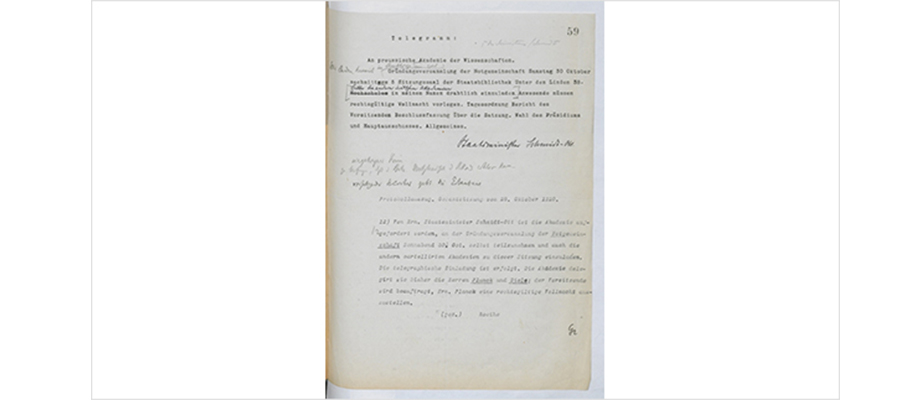

Extract from the statutes of the Notgemeinschaft, October 1920

© Bundesarchiv Koblenz: BAK B 227-540 Hefter 3

In October 1920, five German academies, 35 universities and higher education institutions represented in the Verband der Deutschen Hochschulen, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (KWG, predecessor to the Max Planck Society), the German Federation of Technical and Scientific Organisations (DVT), and the Society of German Researchers and Physicians (GDNÄ) founded the association “Deutsche Gemeinschaft zur Erhaltung und Förderung der Forschung – Notgemeinschaft der deutschen Wissenschaft – E.V.” in order to “avert the danger of the complete collapse of German scientific and scholarly research posed by the present economic crisis”.

The Situation in Science and the Humanities after the First World War

The economic situation in universities and research institutions was very serious indeed after the First World War. Their budgets had not risen since 1913 and an increase in civil servants' salaries and the currency devaluation, which had already begun during the war, simultaneously strained the resources at universities, libraries, museums and research institutions . Improved funding would however have been particularly necessary after the war ended – since it was responsible for the restrictions in the academic sector: young researchers were called up for military service and planned research projects were postponed. Focus was also placed on research that was relevant to war and armaments and some important research areas were downgraded.

This situation was exacerbated by the international isolation of German science and the humanities. The Treaty of Versailles, which laid the blame for the First World War on Germany alone, resulted in a boycott of German science and the humanities: Germany was excluded from international scientific organisations, associations and events, and German research contributions were no longer included in international journals and bibliographies. German academia however was partly to blame for its isolation, since even at the beginning of the war it had discredited itself in the eyes of the international academic community through militaristic pamphlets issued by renowned German scholars.

Even though the German academic and research institutions were supported by different sponsors, they all suffered from considerable underfunding – mainly due to the inflation that began during the First World War.

The individual federal states (Länder) were responsible for the universities and academies of sciences and humanities. The Länder found it hard to continue raising funds for science, the humanities and research. What made matters worse was that finance laws passed by the Reich prevented the Länder from independently compensating for the loss of purchasing power in their cultural budgets.

Some research institutes were maintained via endowment funds, a prominent example of this being the Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft (KWG) founded in 1911. Its research institutes – still well funded in the imperial era and in the First World War – increasingly declined into a precarious financial situation, since the interest income from its foundation capital was no longer sufficient. The institute’s directors drew their salaries from their work as professors at universities and were therefore dependent on state funds.

The Reich also maintained its own research institutions, such as the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (Imperial Physical Technical Institute). It also financed renowned museums like the Romano-Germanic Museum in Mainz and the Deutsches Museum and it maintained major humanities projects, such as the Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Even these institutions were scarcely able to continue operating due to their inadequate budgets.

Industry demanded better equipment, especially for university research, since it was concerned about the next generation of technical researchers for its corporate laboratories. As early as 1916, the chemical industry therefore began to set up funding associations that awarded fellowships.

There were primarily three personalities from research and academic administration who took the initiative in activating/mobilising additional funding – mainly from the Reich – for the ailing academic and research institutions:

Friedrich Schmidt-Ott, President of the Notgemeinschaft from 1920 to 1934

© aus Schmidt-Ott, Erlebtes und Erstrebtes 1860-1950, 1952

Friedrich Schmidt-Ott operated in numerous areas of science, the humanities and cultural policy and was Prussian Minister of Culture from 1917 until November 1918. As organiser of the higher education conferences of the German Länder, he had excellent contacts with universities and higher education institutions. He was furthermore involved in founding the Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft and was treasurer of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry.

Schmidt-Ott was the first president of the Notgemeinschaft der deutschen Wissenschaft (Emergency Association of German Science) and held this office until his forced resignation in 1934. He assumed chairmanship of the founders association of the Notgemeinschaft der deutschen Wissenschaft in 1935.

Fritz Haber

© Creative Commons

The driving force behind formation of the Notgemeinschaft was Fritz Haber. He directed the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Dahlem and was a full member of the Prussian Academies of Sciences and Humanities.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1919. Fritz Haber became vice president of the Notgemeinschaft in 1920; he resigned from his post as a member of the executive committee in May 1933. Link to NS dossier.

Adolf von Harnack

© Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv

Church historian Adolf von Harnack, who was influential in research policy, also distinguished himself in 1920 during preparations for founding the Notgemeinschaft.

He was president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft, director of the Prussian State Library and a full member of the Prussian Academies of Sciences and Humanities and knew the critical situation faced by non-university research institutions from personal experience. He also maintained close contact with Friedrich Schmidt-Ott.

Shortly after the end of the war, the latter used his essay “Die Kulturaufgaben und das Reich” (The Cultural Tasks and the Empire) dated April 1919 to plead for national research funding and for the provision of Reich funds to finance the ailing academia.

In February 1920, the five German academies took their first concrete steps in persuading the Reich to support science and the humanities to a greater extent: They petitioned the National Constituent Assembly for assistance amounting to three million marks. The reasoning composed by Adolf von Harnack for this purpose underlined the importance of science and the humanities to the overall development of Germany:

“The vital necessities of the state include preservation of the few assets it still possesses. German science and the humanities assume a prominent position among these assets. They represent the most crucial prerequisite not only for the preservation of education in Germany and its technology and industry, but also for its reputation and its world position, upon which its prestige and credit in turn depend.”

The Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft was also seeking ways to emerge from the crisis. Closer ties to the economy whilst maintaining academic freedom seemed difficult, and was rejected in internal discussions. In February 1920, the KWG leadership therefore turned to the state with its request and entered into negotiations with the state of Prussia and the Reich regarding greater financial support.

Berliner Tageblatt 7. März 1920, at: http://zefys.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de

© Staatsbibliothek Berlin

Albeit the efforts of the academies and the KWG were only partly successful: the academies’ petition to the National Constituent Assembly could not be processed for formal reasons. The KWG’s negotiations with various ministries dragged on, and it was only in November 1920 that the KWG received additional subsidies from Prussia and the Reich.

To gain a broader hearing beyond government circles, renowned scholars used high-profile newspapers articles to point out the “dire need in science and the humanities”: Fritz Haber’s article “Die gefährdete Forschungsarbeit” (Endangered Research Work) expounded that without additional financial support the KWG’s institutes would be forced to live at the expense of the future and begin using the foundation's capital, which would in any event be exhausted within a few years. Then “these research institutions will resemble the Venetian palaces that stand empty and grant the visitor an interesting perception of past significance.” Adolf von Harnack, director of the Prussian State Library, and physicist Heinrich Rubens from Berlin University had their say in a further article in which they described the vast cost increases experienced in the procurement of books and equipment and in the payment of salaries.

One month later, in March 1920, leading representatives from academia and industry formed a working committee, which was subsequently named the “Notgemeinschaft” (emergency association). This informal working group set itself the task of coordinating joint action to obtain the necessary funds. This took the form of memoranda and applications to parliament, the Reich government and state governments, but also to potential sponsors from the business community. The working committee was founded by the Berlin universities, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes, the Prussian State Library and professional associations. In the summer of 1920, however, the emergency association was expanded to include all universities and technical colleges plus the five academies of sciences and humanities. Friedrich Schmidt-Ott accepted the committee's request to become its chairperson.

Both the Reichsministerium des Innern (RMdI – Reich Ministry of the Interior) and the Reichsfinanzministerium (Reich Ministry of Finance) indicated their willingness to provide financial assistance to the Notgemeinschaft. After negotiations involving the Länder higher education representatives and Reich authorities in spring and summer 1920, Reich Finance Minister Wirth made 20 million marks available in September “to fund the purposes pursued by the Notgemeinschaft der deutschen Wissenschaft”. Wirth stated that the Reich would provide direct funding for pure research purposes, but the upkeep of the universities and academies would still be a matter for the individual states. The Notgemeinschaft’s letter to the RMdI dated 24 September 1920 states that its task consists of “raising funds to preserve German science and the humanities and to achieve a higher degree of efficiency in use of the available funds through appropriate organisation of scientific and academic work, through suitable division of labour and through favourable procurement of research funds.” Quote of Reich Finance Minister Karl Joseph Wirt(externer Link)

Invitation to the inaugural meeting in the form of a telegram

© BBAW: PAW II XIV 31

On 11 October, the RMdI notified the Notgemeinschaft that a further 20 million marks had been requested for financial year 1921.

Following this commitment, an expanded provisional board of the Notgemeinschaft comprising Schmidt-Ott and his associates Eduard Wildhagen, Fritz Haber, Adolf von Harnack and a representative from the RMdI designed the structure for the new organisation: various draft statutes were discussed up to the founding meeting on 30 October. In addition to the general assembly, the most important organs were to be a four-member executive committee, a main committee and specialist committees. The legal forms of association or foundation were up for discussion. The foundation variants were in particular rejected by Fritz Haber against the background of his own experience with the funding model for the Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft, since the interest income from the foundation's assets would be far from sufficient to cover its financial needs.

The inaugural meeting ultimately took place on 30 October 1920 in the Prussian State Library, and the entry in the register of associations followed at the district court of Berlin-Mitte on 7 January 1921 under no. 512566.

The foundation of the “Stifterverband” (Donors’ Association), December 1920

Appeal “To German farmers, merchants, tradespeople and industrialists”, 01/12/1920

© Aus: DFG (Hrsg.) (1985; unveröffentlicht): Vor 65 Jahren: Gründung der Notgemeinschaft der deutschen Wissenschaft. Erinnerungen an die ersten Jahre der Forschungsgemeinschaft

The Notgemeinschaft hoped that it would also be able to win over German industry to contribute financially to the support of research, science and scholarship. To this end, the “Stifterverband der Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft” was founded in December 1920, its Executive Board and Supervisory Board consisting mainly of industrialists, merchants and bank directors. Its purpose was to obtain funds, principally from industry and commerce, in order to support research and teaching.

As a preliminary measure, seven leading bodies of German industry launched a fund-raising campaign “To the German farmers, merchants, tradespeople and industrialists”. This appeal appeared in the press, and 44,000 copies were sent out. Although it was very successful, donations in the years that followed were less than anticipated; furthermore, only the interest payments were paid out to the Notgemeinschaft. It used the money almost exclusively for research fellowships.

Further information

“GEPRIS Historisc(externer Link)” (in German only) is the comprehensive information portal provided by the DFG that makes the history of the DFG and of research between 1920 and 1945 publicly accessible.

Information on literatur(Download) used and sources.