Career Booster North America: Interviews with German researchers in the USA and Canada

Dr. Melanie Ptatscheck

© Philip Nürnberger

(22.06.23) Through its research fellowship program and the Walter Benjamin Program, the DFG supports early-career academics by funding an independent research project abroad and, since 2019, in Germany too. Many of these fellowships are taken up in the USA and to a somewhat lesser extent in Canada. With this series of interviews, we aim to give you an impression of the range of DFG funding recipients. In this edition we take a look at who is behind funding number PT 67.

DFG: Dr. Ptatscheck, thank you very much for taking the time to talk to the DFG’s North American office and sharing with us your fascinating project with street musicians here in New York. But let me start by taking something of a step back. You were born in Bielefeld and went to secondary school there, though your surname is more reminiscent of Vienna or Prague. What do the Ptatschecks do in Bielefeld, and what was your family environment like when you were young, shortly before you took your school-leaving examination at Marienschule der Ursulinen?

Melanie Ptatscheck (MP): Thank you very much for inviting me. This is an interesting change of perspective, by the way – usually I’m the one who invites people to interview and asks them questions for my research. But first let me tell you about the background of the Ptatschecks. My grandparents fled their homeland, Silesia, during the Second World War and arrived in Bielefeld, where the name Ptatscheck is still mainly linked to their bakery business. The smell of freshly baked bread and rolls is very familiar to me. My parents, a master baker and a master confectioner, continued the tradition and ran a shop and café of their own, where I myself worked ever since I was young. Even during my later visiting professorship, I could often be found working behind the counter on weekends. I can tell you: if you don’t get the milk froth right, an academic title won’t be of much use to you either!

DFG: Fresh rolls, sweet pastries and perfectly frothed milk on a cappuccino must have made you very popular during your secondary school days at Marienschule der Ursulinen, right?

MP: Not really. The Ptatschecks – and by that I mean my older brother and myself – were actually more known for our musical activities at school. At that time I was still a very long way from even considering becoming a researcher. Everything revolved around music. School in the morning, music lessons in the afternoon – that’s what my everyday life was like back then. While my friends were on holiday, I was on the road with my ensembles at music rehearsal camps or on concert tours across Europe. I was constantly given time off at school for things like competitions and performances – that was what I was well known for when I was young. I had no doubt back then: I was going to become a professional guitarist.

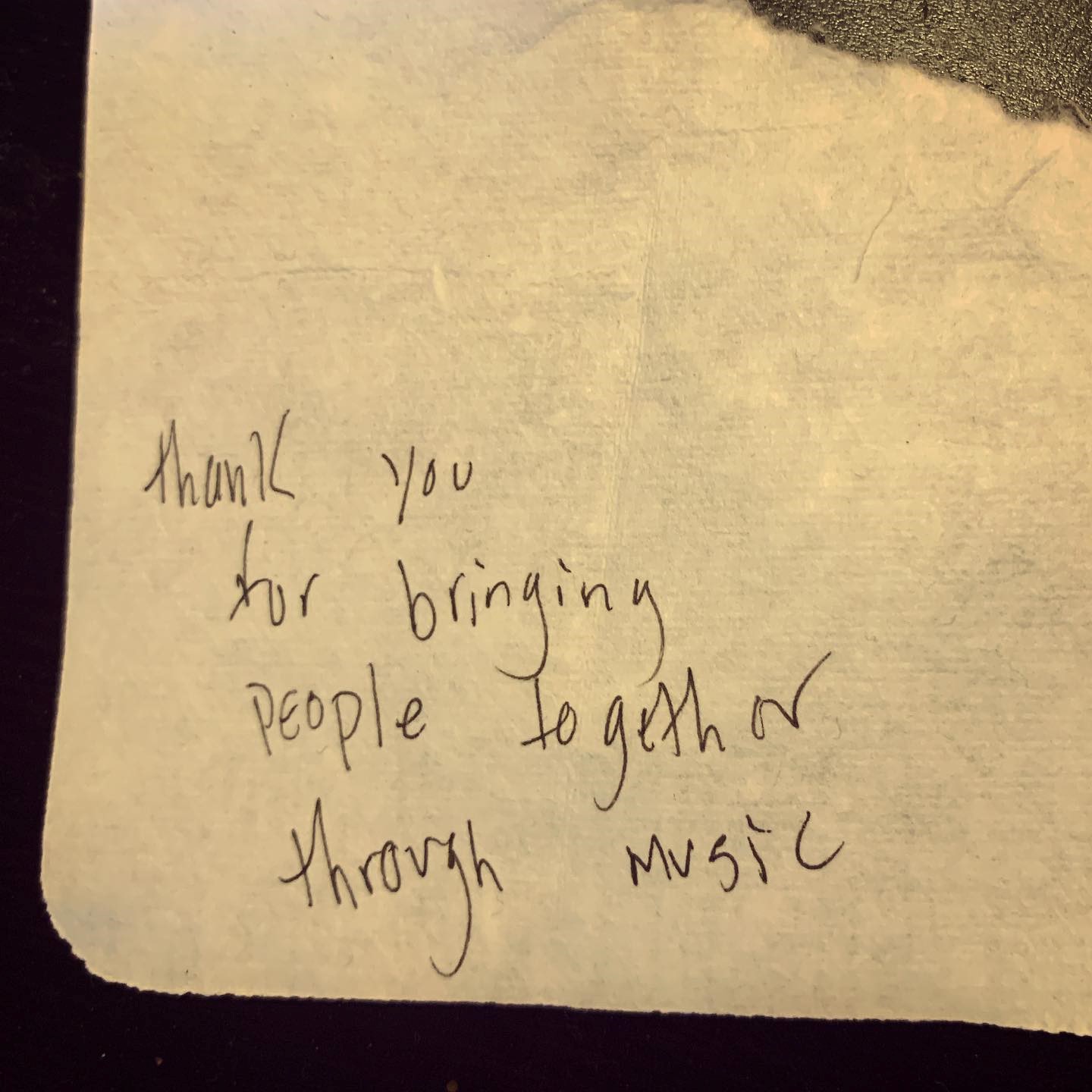

Notiz als Danksagung für einen Straßenmusiker (Anonym)

© Privat

DFG: But you became a researcher, not a musician. What made you change direction?

MP: It happened in my mind. It was never because of my lack of skill or passion for music that I didn’t become a professional musician. The fact is that I was driven by very high expectations and the fear of not being good enough. It got to the stage where my fingers were no longer capable of doing what my mind wanted, so that I was ultimately unable to go up on stage. It wasn’t an issue at all at that time among the people close to me. If you wanted to be “successful,” you had to be able to function. It’s often the same in research, too. So it’s no coincidence that I’ve now made mental health my research focus. Nonetheless, there were a few more detours before that happened.

After graduating from high school, I went into broadcasting. The new plan was to become a journalist. I started out as a freelancer at Radio Bielefeld and studied popular music and media in Paderborn. But during a semester abroad in Vienna, I realized I didn’t really want to be the one writing about people on stage. I still would have much preferred getting back on stage myself. So I undertook a second attempt, this time with the aim of becoming a jazz bass player. I went back to music school and prepared myself for entrance exams to music colleges, swapping elegant concert halls for smoky clubs. But my fear stayed with me. The first time I came to link music with mental health was when I had to prepare a presentation in Vienna about the song “Everything in its right place” by the alternative rock band Radiohead. The artistic struggles with depression suffered by the band’s singer Thom Yorke were the key to a lot of doors I attempted to open afterwards – both for myself personally and in my research. That was when I started writing my own music, which is how I process a lot of what I experience personally. My research projects also always have a personal connection, too.

DFG: In your master’s thesis you looked into how heroin influenced the music of Charlie Parker. What is your personal connection to Parker and heroin?

MP: As a jazz musician, it was an obvious choice for me to tackle a topic that affected my own life. I was interested in musicians’ biographies and found it amazing how many “greats” in popular music history were addicted to heroin, including Parker. During my later research work, I was repeatedly asked whether heroin is still an issue today. Well, it is. Perhaps not as prevalent as in the bebop days of the 1930s-40s or as it was in grunge and alternative rock in the 1980s-90s. But if you follow developments in US hip hop, for example, you’ll see artists with a syringe in their arms in their music videos, bragging about their consumption and putting it on public display. We’re not necessarily talking about heroin here; Fentanyl, Oxycodone, Codeine and Tilidine are currently more in vogue.

Nevertheless, all these substances belong to the group of opioids that were originally used as drugs for anaesthesia and pain relief but are currently seeing a boom as illegal narcotics. And this is not exclusively a US phenomenon either. German rapper Capital Bra released a song in 2019 that’s about drug abuse, quite obviously entitled “Tilidin.” There are even reports that in the period when the song was written there was an increase of about 50 percent in Tilidine prescriptions among the 15-20 age group in Germany. It hasn’t been proven that there is an actual link here, but for me, this is all the more reason to take a socially critical look at drug use in popular music and conduct research in this area in order to raise awareness.

DFG: There has often been speculation about the influence of intoxicants on music production, but in “classical” music it’s always been more about “lighter” drugs such as alcohol. Is it at all possible to identify influences of this kind?

MP: In the field of popular music in particular, the influence of intoxicants on creative processes is indeed an issue. There are interesting studies here on the influence of psychedelics on the music of the Beatles, for example, or on how Jim Morrison’s creativity was linked to his excessive alcohol and drug consumption. And I wouldn’t call alcohol a “lighter” drug. Alcoholism is still a social problem, partly due to the fact that alcohol is sold as a “harmless” lifestyle drug, thereby underestimating its potential for harm. The negative consequences of consumption can also be clearly seen in the music business if you look at musicians such as Amy Winehouse.

In the field of “classical music," the use of drugs and intoxicants such as alcohol, beta-blockers and cocaine (whether for the supposed stimulation of creativity, to combat performance anxiety or to maintain and enhance performance) is an equally widespread phenomenon, though not much research has been done in this area to date, most likely because of the taboos and complexity involved. So I’m unable to give you a general answer to your question. I look at the connection between music and drugs primarily from a social science perspective, focusing on the factors that lead to addiction or mental illness among musicians in general, as well as how these factors influence their living and working conditions.

DFG: A doctoral fellowship from Leuphana University Lüneburg then took you to Los Angeles, where you investigated the link between addictive disorders and the self-concept of rock musicians. “Self-concept” sounds a lot more voluntary than “addiction disorder”. To what extent is the use of hard drugs among musicians part of genre-based folklore, and to what extent is it actual addiction? Can this connection be observed in both male and female musicians?

Die B-Boys/Akrobaten „Funktastic Crew“ performen zusammen mit dem israelischen Singer-Songwriter Yigal Sternklar auf dem Times Square

© Privat

MP: In LA I pursued the whole “sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll” myth cultivated by rock musicians. The decision to consume drugs is usually a voluntary one. But the question here is to what extent people can decide freely at all under certain conditions or whether they’re at the mercy of personal and social conditioning, especially when they’re in the phase of forming their identity. For the interviewees in my study, consumption was not just seen as a community-building ritual that they practiced with like-minded people; it was also a form of self-medication – a welcome way of escaping fears and worries. In addition to traumatic childhood experiences, everyday problems and music-related issues such as the pressure of expectations, anxiety and self-doubt are factors here, as well – as you can see, there’s a link here to my own biography. The initial intoxicating effect of heroin in particular is to numb any kind of physical and psychological pain, so it can also create a sense of freedom and creative power.

This changes, of course, when the experience of intoxication turns into addictive behavior that negatively impacts the user’s life, controlling it or in the worst case even ending it. But at the beginning of their addiction career, the interviewees would block out these negative consequences in their self-concepts of “being a musician” or integrate them as a romantic element as a kind of “27 Club” narrative.

Pop culture and its drug-using representatives are highly influential in terms of the normalization of drug use and the ensuing imitation of behavioral patterns that are hazardous to health. In some areas of popular music, the use of alcohol and drugs was virtually considered part of a pop culture myth, giving rise to various toxic narratives. To go back to Charlie Parker: although his drug use caused him to lose his performing license and he was ultimately no longer fit to play due to the physical and psychological consequences of his alcohol and heroin addiction, the idea that Parker was only able to achieve his musical genius by reaching for the needle still prevailed long after his death.

We see a similar picture with Kurt Cobain, who didn’t go down in history because of his chronic stomach pains, which he said he tried to medicate with heroin and which can actually be seen as having triggered his addiction. Instead, Cobain was stylized as a tragic hero whose heroin addiction was regarded as resulting from depression, hopelessness and the lack of a future. And it was precisely this image that accounted for the typical grunge sound that sold millions of copies worldwide. In addition to certain rituals in the scene, drug use can ultimately also go hand in hand with genre characteristics, along with the potential that this holds in terms of image and marketing.

DFG: So drugs are not an issue in “Schlager” music?

MP: I didn’t say that. There are some performances by Roy Black where he could hardly stay on his feet. You’d rather not know about some of the things that go on backstage – and not just with the performers themselves. I’ve just completed a study on the mental health of songwriters in areas such as the Schlager genre, and there are definitely some dark sides there, too. Nonetheless, Schlager music essentially embodies a positive attitude towards life, related to the needs of its target group. Schlager music is in itself something like a drug that offers a type of escape: a shallow moment of happiness in which the burden of day-to-day life can be forgotten. Self-destructive behavior by performers on stage is not so much a factor here.

The situation is no different in serious music. “Classical music” is not necessarily associated with drug addiction or mental suffering. It is precisely in this context of high culture that we find the origin of the archetype of the “tortured genius”: this didn’t start with Parker or Cobain, but arose long before this in the heroin and genius cult surrounding the “great composers” of Western art music. Mozart himself was considered a “pop star” of his time, and he was also – or perhaps precisely because of this – addicted to alcohol. What’s more, it is interesting to see how the image of the “suffering artist” goes hand in hand with the notion of an artistic self that has masculine connotations. This could also be the reason I was only able to find male interview partners for my study in LA.

But to come back to your second question, female musicians are drug consumers too, of course. Famous examples here include Courtney Love and Janis Joplin. But when female musicians show themselves to be deviant and psychologically vulnerable, the connotation here tends to be negative, in particular because of how they are treated by the media. In contrast, males have a monolpoly on the “sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll” lifestyle; here, excessive behaviour is usually portrayed as positive and admired – as it initially was by my interview partners.

To this day, toxic narratives and beliefs associated with a supposedly successful career as an artist have become entrenched and are reproduced again and again. In another study I did last year on the mental health of pop music students, a 19-year-old singer-songwriter who spoke of excessive drug use, self-harming behavior and suicidal thoughts told me that all this was part of his image as an artist and in his mind part and parcel of being a musician in the first place.

DFG: But that’s not true, is it? The archetype of the tortured genius is just a myth and there’s no link between “creativity” and “madness”?

MP: Above all, it is a dangerous fallacy that has cost some artists their lives. As psychologist Anne Löhr once said in an interview, musicians are not psychos per se. Mental illness, which includes alcohol and drug addiction, can be image-building and drive creative processes for artists, but it’s often the result of their working conditions and living circumstances, as well. Creative individuals are exposed to a lot of factors that cause them psychological stress. Burnout, anxiety, and depression are issues that simply come with business. Risk and stress factors include precarious employment conditions, irregular working hours, financial insecurity, lack of recognition, poor planning ability, lack of a work-life balance, and the pressure to succeed and compete. As in research, there are no reliable career prospects for musicians.

This is why the issue of mental health is now receiving more and more attention in the music industry, not least through institutional processes, such as the establishment of foundations and associations. As a counterpart to international role models such as Help Musicians UK and MusiCares, for example, the German association Mental Health in Music-Verband (MiM) was set up in 2020 as a central point of contact for those involved in the music industry. In terms of research, especially in the field of popular music studies, there’s still a lot of catching up to do in the context of mental health. I’m all the more pleased that the DFG recognizes this and supports my research work.

Natalia Paruz aka „The Saw Lady“ performt im Union Square

© Privat

DFG: You’re currently in New York conducting research into the living conditions of street musicians and the potential lasting effects of the pandemic on this scene. New York is considered a mecca for street music, in particular because the city’s transport authorities organize and promote music on the subway. Is this going to become a new book of yours?

MP: Yes, at least that’s the plan. Though if you look at the stories I sometimes get to experience, I’d probably be better off writing a novel than a research based-book. But research can be exciting, too. Whether a homeless piano player in Washington Square Park who sleeps on his grand piano at night, a breakdance/acrobat group in Times Square that I accompany as a “donation girl,” or the numerous performers in the subway stations, some of whom (like the famous “Saw Lady”) I now count among my friends: in my ethnographic work I try to explore musical life in New York’s urban space through the perspectives of all these individuals.

As you can imagine, it’s not at all easy writing a research book when there are personal destinies behind the “data.” But what really defines my research work is precisely the fact that I’m able to get so close to the people themselves and gain deep insight into their life stories. Not being just a researcher but also a musician myself with my own story to contribute definitely opens doors for me. When it comes to self-image and a musician’s well-being in particular, there are often parallels that help me get closer to my subjects as dialogue partners. Later on, when it comes to the analysis, of course, I need to consistently ensure that I take a step back and reflect on my role as a researcher.

DFG: The Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) has a program called “Music Under New York” for the subway system, which seems to have come to a complete standstill during the pandemic. What are the particular challenges at the moment?

MP: The pandemic had a lasting impact on street music and has definitely left a mark. Even though the subway is open to musicians again, that doesn’t mean to say that everything will go back to usual. For example, there’s the infrastructure like public toilets, which were still closed long after the COVID-19 measures were relaxed, and significantly increased levels of violence and crime. Last year alone there were nine murders in the subway system. MTA Music program participants get special police protection, but even that doesn’t always mean they’re safe from attacks. The tense atmosphere is noticeable among passers-by, too. Subway trains are still not as busy as they used to be before the pandemic. A lot of people avoid larger crowds, and tipping is no longer as generous as it once was. People have also become more accustomed to contactless payment and pay less often with cash. There are now digital payment systems and platforms such as Venmo and Patreon, but this is too much effort for a lot of passers-by in the hustle and bustle of their everyday lives.

The more life returns to routine, the greater the sense of relief is felt in the city. The fact that the subway platforms are finally turning into public concert halls again is helping to restore an element of the typical New York feeling. People dance on the platform at four in the morning, singing and having a good time. The pandemic demonstrated this loss particularly starkly, making people aware of how precious this culture is. My work also ties into discussions around the positive effects of live music on the well-being of music consumers. “We give so much to people,” one of my interviewees once said, showing me a collection of thank-you notes that strangers had slipped him. But during the pandemic he felt overlooked, asking: “What do we get in return? Who will take care of our well-being now?” This critique of the system contains a paradox that is by no means new. A lot of cultural assets such as street music are available for free consumption. But the artists whose work is consumed often lack sufficient support to meet their basic needs. New York artists were offered financial support during the pandemic, too.

But suddenly no longer being able to perform is not necessarily just a question of financial worries. Some of the buskers found themselves confronted with an identity crisis as well. If I’m a musician and I can no longer perform, what does that make me? Here again, self-image comes into play. A musician’s self-image and identity often take years or even decades of emotional and financial investment to establish. For most of these people, it isn’t that easy to let go of the relationship they have with making music or their role in it.

A lot of them did try to find new ways to perform their music nonetheless. And there are some who haven’t returned to the New York subway. Here again I try to find out what paths these people have pursued. Sadly, there are some who decided to end that path – and by that I mean put an end to their lives. These are very isolated cases, fortunately, but nevertheless cautionary examples that raise the question of our choices and obligations in dealing with art and culture in the future. Artists in New York are subject to a high fluctuation, so there’s a lot of interchangeability. Countless artists try to make their breakthrough here – true to Frank Sinatra’s motto, “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere.”

This makes it all the more important for me to go into individual cases and investigate people’s individual life paths in more detail. In June, after a three-year break, there’s finally going to be another MTA Music audition for which musicians have been able to apply. I get to be there behind the scenes. There were even some familiar faces invited who I previously had the pleasure of meeting as a freelance performer in the subway. It’s a little hard to stay neutral about who you’re rooting for to get into the program. Luckily, a jury is responsible for deciding which new members will be able to play at the hotspots in the New York subway in the future as part of the MTA Music program. I can’t wait to see how these people are going to bring the subway to life again with their music, and what their motivation is.

Colin Huggins aka „The Piano Man of Washington Square Park

© Colin Huggins

DFG: What are your plans for the near future and the next five years?

MP: Not having a plan is often the best plan – that’s something I’ve learned here in New York. They say the city never sleeps, and rightly so. No two days are the same here and unpredictable things often happen. In terms of my fieldwork, this means being as open as possible and taking advantage of opportunities for an encounter whenever they arise. At the same time, I also have to plan carefully when it comes to publishing the results of my work and attending conferences, for example. This year alone, I’ll be travelling to give lectures in the USA, Canada, Germany, Austria, and the UK. As you can see, there’s a touring life in research, too.

But long-term planning is not entirely absent. I’m already working on a proposal for a follow-up project. It’s an enormous privilege to be a fellowship holder under the Walter Benjamin Program. The fact that I’m not just supported as a person but also in my research projects and topics makes me feel very motivated to continue on this path with the DFG. I see my future as a researcher in the field of health humanities, in which I’d like to represent popular music studies. I don’t want to give too much away yet, but it’ll be about exploring health narratives in popular music. I’m planning an Emmy Noether independent junior research group for this purpose, in which I’d also like to support other researchers in the qualification phase of their career. The year before last. I established the Early Career Women* in Popular Music network with my colleague Monika Schoop. So promoting women in research is a particular passion of mine, too.

Speaking of passion: maybe in the end I will switch back to plan A after all and you’ll see me back up on the world stage once again. Every now and then I still carry on writing my big hit in my spare time. In any case, it’s interesting for me to be able to see a lot of the institutional stages that I wasn’t able to play on as a musician and view them from a different perspective. I did some research at the Baden-Württemberg Pop Academy, for example, and was active as a lecturer there. And I’ve even been awarded a visiting professorship since then at Cologne University of Music and Dance. Sometimes you just have to take a detour.

DFG: You’re now at home – or have been basically at home – in a lot of different places. What are your lasting impressions, and what do you remember more or less fondly?

MP: After leaving secondary school I wanted to get as far away from Bielefeld as possible – and initially ended up in the cosmopolitan city of Paderborn. It took a few attempts before I finally made it across the pond. Among other places, I once lived in Vienna for a while, where various things coincided – the plan to become a bass player, a soft spot I had for the Viennese dialect at the time, and two semesters abroad in musicology. After that, Los Angeles was something of a self-discovery trip, both scientifically and personally. Getting lost was also part of my path too, of course, although these excursions have definitely left a positive mark on my research CV.

As I mentioned before, getting the milk to froth perfectly on weekends can be quite relaxing for the mind. I also completed a second part-time master’s degree in health sciences in between, something I wouldn’t see as a lack of planning but more as a way of fully embracing an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approach – not least as “strategic” career planning, too. After all, it was due to the DFG’s support that my path took me here to New York – and for that I am very proud and more than grateful. New York has become my current home. The thought of returning to my home town at some point certainly seems rather far-fetched at the moment given my “bohemian lifestyle” here, as my great-aunt once put it. But that’s something else I’ve learned: never say never.

DFG: If your research career were to take you back to the provinces, far away from the bohemian lifestyle, how would you resolve these conflicting goals?

MP: If it felt right for me, there wouldn’t be any conflict. I can certainly imagine swapping the big cities of the world for a log cabin on a fjord in Sweden one day. But it’s important to me to be able to make this decision myself. Self-determination is one of the top priorities in terms of my academic trajectory, too – as well as an enormous privilege. Research is not exactly synonymous with security and wide-ranging choices, especially when it comes to job offers. But the fact that I’m talking to you here now also shows that where there’s a will, there’s a way. In addition to my stubbornness and curiosity, my driving force has always been my passion for the subjects that move me personally and that give me a sense of purpose.

I still remember what my PhD supervisor said when I started my doctorate and was raving about my wild research plans in Los Angeles: “Research has nothing to do with passion.” I learned a lot from him, but in that respect, I like to think I proved him wrong. We’ve become good friends, but every message I send him (“With love from Manhattan”) is always accompanied by a little grin. And who knows, maybe one day as a professor emeritus I’ll be sending my regards from my very own café in Bielefeld, where I’m passionate about creating the perfect milk froth.

DFG: Thank you very much for the prospect of a perfect milk froth in a Bielefeld café as a kind of alternative career path! But we sincerely hope that before then plan A will work out, or admission to the Emmy Noether Program or a comparable research group leadership position. We look forward to your upcoming publication on street music in New York City and wish you all the very best, both for your career and your private endeavors.